What Animals Are On The Ishtar Gate

The Ishtar Gate was the eighth gate to the inner metropolis of Babylon[ citation needed ] (in the area of present-day Hillah, Babil Governorate, Iraq). It was constructed circa 575 BCE by order of King Nebuchadnezzar Ii on the northward side of the metropolis. It was part of a grand walled processional manner leading into the urban center. The walls were finished in glazed bricks mostly in blue, with animals and deities in low relief at intervals, these also made up of bricks that are molded and colored differently.

The High german archaeologist Robert Koldewey led the digging of the site from 1904 to 1914.

Subsequently the terminate of the First World State of war in 1918, the smaller gate was reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum. The gate is l feet (15.2 meters) high, and the original foundations extended another 45 feet (13.7 meters) hugger-mugger.[one] The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum is not a complete replica of the entire gate. The original structure was a double gate with a smaller frontal gate and a larger and more grandiose secondary posterior department.[two] The only section on display in the Pergamon Museum is the smaller frontal segment.[iii]

Other panels from the facade of the gate are located in many other museums around the world, including various European countries and the United states of america.

The façade of Iraqi embassy in Beijing, China includes a replica of the Ishtar Gate.[4]

History [edit]

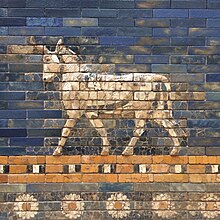

One of the mušḫuššu dragons from the gate

King Nebuchadnezzar 2 reigned 604–562 BCE, the peak of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. He is known as the biblical conqueror who captured Jerusalem.[five] He ordered the structure of the gate and dedicated it to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar. The gate was constructed using glazed brick with alternating rows of bas-relief mušḫuššu (dragons), aurochs (bulls), and lions, symbolizing the gods Marduk, Adad, and Ishtar respectively.[6]

The roof and doors of the gate were made of cedar, co-ordinate to the dedication plaque. The bricks in the gate were covered in a blue glaze meant to represent lapis lazuli, a deep-blue semi-precious stone that was revered in antiquity due to its vibrancy. The blueish glazed bricks would have given the façade a gem-similar polish. Through the gate ran the Processional Way, which was lined with walls showing about 120 lions, bulls, dragons, and flowers on yellow and black glazed bricks, symbolizing the goddess Ishtar. The gate itself depicted only gods and goddesses. These included Ishtar, Adad, and Marduk. During celebrations of the New year, statues of the deities were paraded through the gate and downwardly the Processional Style.[ citation needed ]

The gate, existence role of the Walls of Babylon, was considered one of the original Seven Wonders of the World. It was replaced on that list by the Lighthouse of Alexandria from the third century BC.[7]

Design [edit]

The forepart of the gate has a low relief blueprint with a repeated pattern of images of two of the major gods of the Babylonian pantheon. Marduk, the national deity and chief god, with his retainer dragon Mušḫuššu. is depicted as a dragon with a snake-like caput and tail, a scaled body of a lion, and powerful talons for back feet. Marduk was seen as the divine champion of good against evil, and the incantations of the Babylonians oftentimes sought his protection.[8]

An aurochs higher up a bloom ribbon; missing tiles are replaced

The second god shown in the pattern of reliefs on the Ishtar Gate is Adad (likewise known as Ishkur), whose sacred animal was the aurochs, a at present-extinct ancestor of cattle. Adad had power over destructive storms and beneficial rain. The design of the Ishtar Gate likewise includes linear borders and patterns of rosettes, often seen as symbols of fertility.[8]

The bricks of the Ishtar gate were fabricated from finely textured clay pressed into wooden forms. Each of the brute reliefs was also made from bricks formed by pressing clay into reusable molds. Seams betwixt the bricks were carefully planned non to occur on the optics of the animals or any other aesthetically unacceptable places. The bricks were sun-dried so fired in one case before glazing. The clay was brownish red in this bisque-fired country.[ix]

The background glazes are mainly a vivid blue, which imitates the color of the highly prized lapis lazuli. Gold and chocolate-brown glazes are used for animal images. The borders and rosettes are glazed in black, white, and gold. It is believed that the coat recipe used found ash, sandstone conglomerates, and pebbles for silicates. This combination was repeatedly melted, cooled, and then pulverized. This mixture of silica and fluxes is called a frit. Color-producing minerals, such equally cobalt, were added in the final glaze formulations. This was then painted onto the bisque-fired bricks and fired to a higher temperature in a glaze firing.[9]

The creation of the gate out of wood and dirt glazed to look like lapis lazuli could possibly be a reference to the goddess Inanna, who became syncretized with the goddess Ishtar during the reign of Sargon of Akkad. In the myth of Inanna's descent to the underworld, Inanna is described equally donning seven accoutrements of lapis lazuli[ten] [11] symbolizing her divine power. One time captured by the queen of the underworld, Inanna is described every bit being lapis lazuli, argent, and wood,[12] ii of these materials being key components in the construction of the Ishtar Gate. The cosmos of the gate out of forest and "lapis lazuli" linking the gate to being part of the Goddess herself.

Later the glaze firing, the bricks were assembled, leaving narrow horizontal seams from 1 to half-dozen millimeters. The seams were and so sealed with a naturally occurring black gummy substance chosen bitumen, similar modernistic cobblestone. The Ishtar Gate is only i small-scale part of the design of ancient Babylon that as well included the palace, temples, an inner fortress, walls, gardens, other gates, and the Processional Way. The lavish city was decorated with over 15 meg baked bricks, according to estimates.[9]

The master gate led to the Southern Citadel, the gate itself seeming to exist a part of Imgur-Bel and Nimitti-Bel, two of the most prominent defensive walls of Babylon. At that place were iii chief entrances to the Ishtar Gate: the cardinal entrance which contained the double gate construction (2 sets of double doors, for a fourfold door structure), and doors flanking the master entrance to the left and right, both containing the signature double door structure.[13]

Ishtar Gate and Processional Style [edit]

Model of the main procession street (Aj-ibur-shapu) towards Ishtar Gate

In one case per year, the Ishtar Gate and connecting Processional Mode were used for a New year's day's procession, which was part of a religious festival celebrating the showtime of the agricultural year. In Babylon, the rituals surrounding this vacation lasted twelve days. The New year's day's celebrations started immediately after the barley harvest, at the fourth dimension of the vernal equinox. This was the first day of the ancient month of Nisan, equivalent to today's date of March xx or 21.[eight]

The Processional Way, which has been traced to a length of over half a mile (800 meters), extended due north from the Ishtar Gate and was designed with brick relief images of lions, the symbol of the goddess Ishtar (also known as Inanna) the war goddess, the dragon of Marduk, the lord of the gods, and the bull of Adad, the storm god.[xiv] Worshipped equally the Mistress of Sky, Ishtar represented the power of sexual allure and was idea to be savage and adamant. Symbolized by the star and her sacred fauna, the lion, she was besides the goddess of war and the protector of ruling dynasties and their armies. The idea of protection of the metropolis is further incorporated into this gateway design by the utilize of crenelated buttresses forth both sides to this archway into the city.[8]

Friezes with threescore ferocious lions representing Ishtar decorated each side of the Processional Fashion, designed with variations in the color of the fur and the manes. On the east side, they had a left foot forward, and on the west side, they had the right foot forward. Each king of beasts was made of forty-six molded bricks in eleven rows.[nine] The lion is pictured upon a blue enameled tile background and an orange coloured border that runs along the very bottom portion of the wall. Having a white body and yellow mane, the panthera leo of Ishtar was an apotheosis of brilliant naturalism that farther enhanced the celebrity of Babylon'southward Procession Street.[14] [xv]

The purpose of the New year's day's holiday was to affirm the supremacy of Marduk and his representative on World, the rex, and to offering cheers for the fertility of the land.[viii]

The Processional Way was paved with large stone pieces set up in a bed of bitumen and was up to 66 feet (20.1 meters) wide at some points. This street ran from the Euphrates through the temple district and palaces and onto the Ishtar Gate.[16]

Inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II [edit]

The cuneiform inscription of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

The inscription of the Ishtar Gate is written in Akkadian cuneiform in white and blue glazed bricks and was a dedication past Nebuchadnezzar to explain the gate's purpose. On the wall of the Ishtar Gate, the inscription is 15 meters tall by 10 meters broad and includes threescore lines of writing. The inscription was created around the same time as the gate's construction, around 605–562 BCE.[17]

Inscription:

Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon, the pious prince appointed by the will of Marduk, the highest priestly prince, beloved of Nabu, of prudent deliberation, who has learnt to embrace wisdom, who fathomed Their (Marduk and Nabu) godly being and pays reverence to their Majesty, the untiring Governor, who always has at heart the care of the cult of Esagila and Ezida and is constantly concerned with the well beingness of Babylon and Borsippa, the wise, the humble, the flagman of Esagila and Ezida, the first born son of Nabopolassar, the King of Babylon, am I.

Both gate entrances of the (urban center walls) Imgur-Ellil and Nemetti-Ellil following the filling of the street from Babylon had become increasingly lower. (Therefore,) I pulled down these gates and laid their foundations at the h2o table with cobblestone and bricks and had them fabricated of bricks with blue rock on which wonderful bulls and dragons were depicted. I covered their roofs by laying regal cedars lengthwise over them. I fixed doors of cedar wood adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor and so that Mankind might gaze on them in wonder.

I let the temple of Esiskursiskur, the highest festival house of Marduk, the lord of the gods, a place of joy and jubilation for the major and minor deities, be built firm similar a mountain in the precinct of Babylon of asphalt and fired bricks.[18]

Earthworks and display [edit]

A reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate and Processional Fashion was congenital at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin out of textile excavated by Robert Koldewey.[19] Information technology includes the inscription plaque. It stands xiv m (46 ft) high and 30 1000 (100 ft) wide. The digging ran from 1902 to 1914, and, during that fourth dimension, 14 m (45 ft) of the foundation of the gate was uncovered.

Photo of the in situ remains from the 1930s of the earthworks site in Babylon

Claudius Rich, British resident of Baghdad and a cocky-taught historian, did personal research on Babylon because it intrigued him. Acting as a scholar and collecting field data, he was determined to discover the wonders to the aboriginal world. C. J. Rich's topographical records of the ruins in Babylon were the get-go ever published, in 1815. It was reprinted in England no fewer than 3 times. C. J. Rich and nigh other 19th-century visitors thought a mound in Babylon was a regal palace, and that was eventually confirmed by Robert Koldewey'due south excavations, who institute two palaces of King Nebuchadnezzar and the Ishtar Gate. Robert Koldewey, a successful German excavator, had washed previous work for the Imperial Museum of Berlin, with his excavations at Surghul (Aboriginal Nina) and Al-hiba (ancient Lagash) in 1887. Koldewey's part in Babylon's earthworks began in 1899.[twenty]

The method that the British were comfortable with was excavating tunnels and deep trenches, which was damaging the mud brick architecture of the foundation. Instead, it was suggested that the excavation team focus on tablets and other artefacts rather than pick at the aging buildings. Despite the subversive nature of the archaeology used, the recording of data was immensely more thorough than in previous Mesopotamian excavations. Walter Andrea, i of Koldewey'south many administration, was an architect and a draftsman, the first at Babylon. His contribution was documentation and reconstruction of Babylon, and so later, the smuggling of the remains out of Iraq and into Germany. A minor museum was built at the site, and Andrea was the museum'due south get-go director.

Equally the German Oriental Society had provided such large funding for the projection, the German language archeologists involved felt that they needed to justify the cost past smuggling much of the cloth back to Deutschland. For case, of the 120 lion friezes along the Procession Street, the Germans took 118.[21] Walter Andrea played a cardinal role in this endeavor using the strong links (or wasta) that he had cultivated with High german intelligence officers and with local Iraqi tribal sheikhs. The Gate's ceramic pieces were disassembled according to a complex numbering system and were then packed in harbinger in coal barrels in order to disguise them.[22] These barrels were then transported down the Euphrates River to Shatt al-Arab, where they were loaded onto German ships and taken to Berlin.[23]

The rebuilding of Babylon's Ishtar Gate and Processional Way in Berlin was one of the most complex architectural reconstructions in the history of archaeology. Hundreds of crates of glazed brick fragments were advisedly desalinated and so pieced together. Fragments were combined with new bricks fired in a especially designed kiln to re-create the correct color and end. Information technology was a double gate; the part that is shown in the Pergamon Museum today is the smaller, frontal function.[24] The larger, back part was considered too large to fit into the constraints of the structure of the museum; it is in storage.

Pergamon Museum, Ishtar gate

Parts of the gate and lions from the Processional Fashion are in various other museums around the world. Simply four museums caused dragons, while lions went to several museums. The Istanbul Archeology Museum has lions, dragons, and bulls. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, Denmark, has ane king of beasts, ane dragon and one balderdash. The Detroit Institute of Arts houses a dragon. The Röhsska Museum in Gothenburg, Sweden, has one dragon and one lion; the Louvre, the State Museum of Egyptian Fine art in Munich, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Oriental Institute in Chicago, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Oasis, Connecticut, each have lions. Ane of the processional lions was recently loaned by Berlin's Vorderasiatisches Museum to the British Museum.[25]

A smaller reproduction of the gate was built in Iraq under Saddam Hussein as the archway to a museum that has not been completed. Along with the restored palace, the gate was completed in 1987. The construction was meant to emulate the techniques that were used for the original gate. The replica appears like to the restored original but is notably smaller. The purpose of the replica's construction was an attempt to reconnect to Iraq's history.[26] Damage to this reproduction has occurred since the Iraq War (run into Touch on of the U.Due south. military).

Controversy and attempted repatriation [edit]

The acquisition of the Ishtar Gate by the Pergamon Museum is surrounded in controversy every bit the gate was excavated as role of the excavation of Babylon, and immediately shipped off to Berlin where it remains to this day. The government of Iraq has petitioned the High german regime to return the gate many times, notably in 2002[27] too every bit in 2009.[28] The Ishtar Gate is frequently used as a prime number example in the debate regarding repatriating artifacts of cultural significance to countries affected by war and whether these pieces of material civilization are better off in a safer surround where they could exist preserved. The case in the instance of the Ishtar Gate is concerning its condom in regards to the aftermath of the Iraq War, and whether or not the gate would exist safer remaining at the Pergamon Museum.[29]

Gallery [edit]

-

Robert Koldewey's Imagining of what a complete and reconstructed Ishtar Gate would look similar.

-

Model of the gate; the double construction is clearly recognisable.

-

The Processional Manner equally reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum, Berlin

-

-

1 of the striding lions from the Processional Way.

-

Tiles to the side of the gate

-

The Ishtar Gate replica, much smaller than the original, in Babylon in 2004

-

Mušḫuššu dragon in Istanbul Aboriginal Orient Museum Ishtar Gate

-

Mušḫuššu dragon in Istanbul Aboriginal Orient Museum Ishtar Gate

-

Panthera leo in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate

-

Lion in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate

-

Balderdash in Istanbul Aboriginal Orient Museum Ishtar Gate

References [edit]

- ^ Podany, Amanda (2018). Aboriginal Mesopotamia: Life in the Cradle of Civilization. The Keen Courses. p. 213.

- ^ Garcia, Brittany. "Ishtar Gate". Earth History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Luckenbill, D. D. "Review: The Excavation of Babylon". The American Journal of Theology. 18: 420–425. doi:10.1086/479397 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Cathay's Republic of iraq Oil Problem". Fortune. June thirty, 2014.

- ^ "Panel with striding lion | Work of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art". The Met'due south Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . Retrieved 2017-11-28 .

- ^ Kleiner, Fred (2005). Gardner's Art Through the Ages. Belmont, CA: Thompson Learning, Inc. p. 49. ISBN978-0-xv-505090-7.

- ^ Clayton, Peter A.; Toll, Martin (2013-08-21). The Seven Wonders of the Ancient Globe. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN9781136748103 . Retrieved xi Baronial 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bertman, Stephen (vii July 2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. pp. 130–132. ISBN978-0195183641.

- ^ a b c d King, Leo (2008). "The Ishtar Gate". Ceramics Technical. No. 26 (2008): 51–53. Retrieved 21 Nov 2017.

- ^ Kramer, Samuel Noah (1961). Sumerian Mythology: A Report of Spiritual and Literary Achievement in the Tertiary Millennium B.C.: Revised Edition. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN978-0-8122-1047-7.

- ^ Wolkstein, Diane (1983). Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Globe: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York Metropolis, New York: Harper&Row Publishers. ISBN978-0-06-090854-6.

- ^ George, A. R. "Observations on a Passage of "Inanna'due south Descent"". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 37: 112 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Koldewey, Robert (1914). The Excavations at Babylon. Macmillan and Company. pp. xxx–twoscore.

- ^ a b R.P.D. (October 1932). "The Lion of Ishtar". Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale University. 4 (3): 144–147. JSTOR 40513763.

- ^ "Console with Striding King of beasts". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2018.

- ^ Stokstad, Marilyn (2018). Fine art History. Upper Saddle River: Pearson. pp. 43–44. ISBN9780134479279.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab (2017). Mesopotamia: Ancient Art and Architecture. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. p. 280. ISBN978-0-500-51917-2.

- ^ Marzahn, Joachim (1981). Babylon und das Neujahrsfest. Berlin: Berlin : Vorderasiatisches Museum. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Maso, Felip (five Jan 2018). "Inside the 30-Year Quest for Babylon'due south Ishtar Gate". National Geographic. Archived from the original on July three, 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Bilsel, Can (2012), Antiquity on display : regimes of the authentic in Berlin'due south Pergamon Museum, Oxford University Press, ISBN978-0-xix-957055-3

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (May 4, 2002). "Iraq appeals to Berlin for return of Babylon gate". The Guardian.

- ^ Khairy Al-Haider, Hamed (July 7, 2021). "بوابة عشتار .. كيف نقلت الى المانيا ؟!".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Muzaffar Al-Adhamy, Muhammad (July 25, 2020). "كيف سرق الألمان بوابة عشتار من بابل؟". YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Bernbeck, Reinhard (5 Jan 2009). "The exhibition of architecture and the compages of an exhibition". Archaeological Dialogues. 7 (2): 98–125. doi:10.1017/S1380203800001665.

- ^ "British Museum Website". Archived from the original on Jan 27, 2014.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Neil (Baronial 19, 2003). "Hussein's Babylon: A Beloved Atrocity". The New York Times . Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (iv May 2002). "The Guardian". Iraq appeals to Berlin for return of Babylon gate . Retrieved xi Nov 2020.

- ^ Mohammed, Zainab (5 November 2009). "History News Network, George Washington University". Is Republic of iraq correct to reclaim the Ishtar Gate from Frg? . Retrieved ten November 2020.

- ^ Arregui, Aníbal (2018). DEcolonial Heritage: Natures, Cultures, and the Asymmetries of Memory. Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. p. 10.

- Matson, F.R. (1985), Compositional Studies of the Glazed Brick from the Ishtar Gate at Babylon, Museum of Fine Arts. The Research Laboratory, ISBN978-0-87846-255-1

External links [edit]

- Pictures of panthera leo & dragon at the Röhsska museum, Gothenburg

- 60 pictures of the brute panels in Istanbul Museum

- Neo-Babylonian Art: Ishtar Gate and Processional Way, Smarthistory

Coordinates: 32°32′36″North 44°25′20″Eastward / 32.54333°N 44.42222°E / 32.54333; 44.42222

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ishtar_Gate

Posted by: mcleanyoureput.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animals Are On The Ishtar Gate"

Post a Comment